Amongst the most pleasurable aspects of the life I’ve created for myself here in Oaxaca are the literature workshops I get to give in this venerable building, the Biblioteca Henestrosa, so named because it houses the book collection of Oaxaca’s centenarian writer Andrés Henestrosa, chronicler of indigenous legends and transcriber of the Zapotec language to the Latin alphabet. Here are a pair of photos, one of the exterior and the other of the room where I give my workshops:

The workshop I’m kicking off this year with is called “A Tour of Italian literature”, what in the States would be known as a survey course. And at four hours a week over four months, 64 hours of class time in total, it really is more of a course than a workshop. But without the bureaucracy, the grading and the diplomas. The students are there because they want to be and for the love of learning, not because they expect to get something else out of it, be it course credits or a certificate: such a salutary difference from my days at the University. And the mixture of ages and experience – from college students to retirees, breaking up the artificial and isolating segregation by age our schools are so proficient at – adds a spirit of camaraderie and generational exchange to the educational mix. I love it.

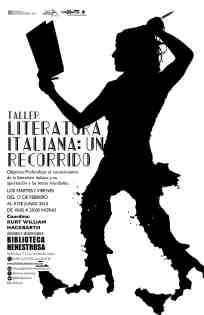

Besides paying me to give the workshops (thus making it free for the students), the Biblioteca also has a great team of graphic designers making up the posters that go up around town promoting their events. Here, incidentally, is the poster for my workshop:

The first question that confronts anyone when designing a course that purports to cover so much ground is, simply, where to start? With Dante’s dolce stil nuovo, with Petrarch’s sonnets to Laura? I did, in fact, start with a sonnet, but one with quite a distinct tone: “S’i fosse foco” by Cecco Angioleri. Here it is, with English translation, commentary and as set to music by Fabrizio de André, whose song “Fiume Sand Creek” song I referenced in my earlier post, A Sand Creek Moment. This English translation of it admirably attempts to reproduce both the rhyme scheme and a consistent 10-syllable meter:

The first question that confronts anyone when designing a course that purports to cover so much ground is, simply, where to start? With Dante’s dolce stil nuovo, with Petrarch’s sonnets to Laura? I did, in fact, start with a sonnet, but one with quite a distinct tone: “S’i fosse foco” by Cecco Angioleri. Here it is, with English translation, commentary and as set to music by Fabrizio de André, whose song “Fiume Sand Creek” song I referenced in my earlier post, A Sand Creek Moment. This English translation of it admirably attempts to reproduce both the rhyme scheme and a consistent 10-syllable meter:

If I were fire, I would consume the world;

If I were wind, then I would blow it down;

If I were water, I would make it drown;

If I were God, t’would to the depths be hurled.

If I were Pope, I’d have a lot of fun

with how I’d make all Christians work for me;

If I were emperor, then you’d really see –

I’d have the head cut off of everyone.

If I were death, then I’d go to my father;

If I were life, I’d not abide with him;

And so, and so, would I do to my mother.

If I were Cecco – as in fact I am –

I’d chase the young and pretty girls; to others

Would I leave the lame or wrinkled dam.

If I were fire, I would consume the world;

If I were wind, then I would blow it down;

If I were water, I would make it drown;

If I were God, t’would to the depths be hurled.

My choice for starting with Angioleri’s famous sonnet was hardly a disinterested one: like De André, I love the irreverence and iconoclasm of it. Such a far cry from our standard notions of the Medieval era as a time of piety, plainsong and popes burning heretics at the stake. It was effective in catching the attention of my students right out of the starting gate, as well (and, to be fair, plenty of Italian lit anthologies start with it, so my choice was hardly original). From there, continuing in a straight line of irreverence, Boccaccio’s Decameron – that racy, bawdy treasure trove of tales that became an instant bestseller amongst the rising Florentine merchant class – presented itself as the next logical choice. Here are nuns organizing a schedule to make love with their gardener; an overprotected young girl persuading her parents to let her sleep out on the roof in order to rendez-vous with her lover; a sinner convincing a friar on his deathbed that he was a saint and becoming posthumously venerated as such; a man returning from the afterlife to visit his best friend in order to inform him that sleeping with your comadre doesn’t count as a sin; a lascivious priest attempting to transform a credulous peasant’s wife into a mare by fondling her and ultimately, “pinning a tail on her”… You get the idea. In choosing which of the hundred stories to assign, I was guided by the ones Pier Paolo Pasolini chose when making his film version of The Decameron, which we subsequently watched.

As Mario Vargas Llosa says in his account of the literary pilgrimage he made to Boccaccio’s hometown of Certaldo, it was the Black Death that got this bookish intellectual, Latinist, Hellenist, and yes, even theologian, to put down his books and not only to get out into the street to learn the stories of the people, but to write them down in their language: the Tuscan of Florence, later to become known to us as “Italian”. Thus, classical learning and a thorough understanding of medieval verse became wedded to a corpus of popular storytelling stretching back through the Arab world to ancient India. And the back of Latin had been broken to allow literature in “vulgar” languages to flourish. The Western short story had been born.

Let others begin with Heaven and Hell, divine allegory and lyric yearning. I’m following Boccaccio’s lead, out the door and into the street; see what kind of trouble I can get into.