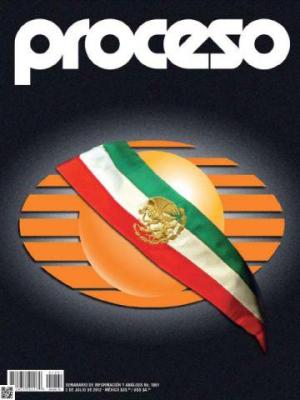

A deeply unpopular privatization of Mexico’s energy industry. A highly unpopular president mired in a series of high-profile gaffes and scandals. A series of unresolved killings in places with names like Ayotzinapa, Apatzingán, Tlatlaya and Tanhuato. An economy stuck in underdrive. Violence, insecurity, and a general sense that things are getting worse. So how, in God’s name, did the ruling PRI party win this last Sunday’s midterm elections? Here are 10 reasons that should clear things up a little:

1. They didn’t actually win. The PRI’s vote share, both in terms of percentage and eventual seats in the Camara de Diputados, was actually down from the last elections in 2012. The fact that they will have a majority in the lower house in the coming session is due to…

2. The PRI’s alliance with the Green Party. Knowing that they were likely to be the victims of a protest vote, the PRI poured resources into their affiliate, the Greens. Despite its deceptive name, the Green Party has nothing whatsoever to do with ecology, but is simply a stooge of both the PRI and the Televisa broadcasting company (see point #9). The Greens racked up a series of electoral law violations, including lavish overspending, the distribution of personalized, discount debit cards to would-be voters, and a failure to respect the three-day campaign blackout before the election: on polling day, a series of hack celebrities were trundled out to tweet in favor of the Greens, tweets which received an estimated 100 million views. And the strategy, literally, paid off: the Greens racked up some 7% of the vote. It is fair to assume that a substantial number of those voters were not aware that they were effectively voting for the PRI, but their votes were enough to give the ruling party its majority. And all of this was made possible thanks to…

3. The Haplessness of the National Electoral Institute. Faced with the avalanche of irregularities committed by the Greens, the National Electoral Institute (INE) did what they always do: fined them. To which the Greens shrugged and said, “Fine”. With so much to gain by breaking the rules, any fines generated are simply factored into the electoral accounting. It’s all public money, anyway. As I pointed out in my previous post, the parties this year will receive 5,356 million pesos in public financing; with such a bonanza of funding at their disposal, what’s a little more or less? The real sanction that the INE could mete out would be to revoke the Green Party’s registro, their party registry and the public financing that goes with it. But when citizens and representatives of the other parties brought this request to the INE, it refused to even consider it. And even if they did, the Greens could always count on…

4. The Haplessness of the Federal Electoral Tribunal. The Federal Electoral Tribunal (TEPJF is its juicy acronym in Spanish) has the final say on all electoral questions in the nation. It was the court responsible for rubber-stamping the electoral frauds of 2006 and 2012. Its justices are the highest-paid “public servants” in the nation, earning, including benefits, 563,416 pesos ($40,244 dollars) a month. That’s per month, not per year. During this electoral cycle, it busied itself by swatting down, often without debate, several of the fines against the Greens imposed by the INE for violations such as the transmission of political ads veiled as “legislative reports” and taking advantage of federal programs in campaign advertising.

5. The Inequities of the Voting System. Mexico uses the relative majority, or first-past-the-post voting system to elect 300 of its 500 deputies. The unfairness of first-past-the-post has been widely discussed, primarily because of how unrepresentative it is: candidates can win their districts, and parties can win elections, without winning anywhere near a majority of votes cast. All it takes is that they win one more vote than their closest rival. In the case of Mexico, with some ten parties in contention this time around, winning parties were able to win their districts with vote percentages, in competitive districts, in the twenties percent. (Add to this that the primary supposed benefit of first-past-the-post, the direct link between the individual representative and his or her constituency, hardly applies to Mexico, where the representative-constitutency link is virtually non-existent). First-past-the-post was particularly merciless with Mexico’s sadly divided left, with four nominally center-left parties drawing and quartering the vote: the PRD (10.74%), Morena (8.37%), Movimiento Ciudadano (6.11%) and the Worker’s Party (2.82%). Total them up and the left pulls just about level with the PRI’s share.

6. Low Voter Turnout. Some 47% of registered voters turned out for the midterm elections this year. Because overall turnout was about on par with previous midterms, this is being spun as some kind of democratic success story. In truth, the PRI “victory” looks all that much more hollow. Of the 47% of voters that bothered to turn out, the PRI won 29% of that. As the table here shows, this actually brings the PRI victory down to about 14% of registered voters or, if we take into account the 5% who spoiled their votes (making “none of the above” the third or fourth-place finisher in a number of states), even less. Why less? Because of…

7. The Catch in the Electoral Law. According to Mexican Electoral Law. spoiled votes are taken into account when calculating overall turnout, but when calculating the seats, benefits and money assigned to the parties, only “valid” votes – that is, votes clearly cast for someone – are taken into account. So ironically, although vote spoilers were attempting to voice their protest against the system in the clearest, most forceful way possible, the PRI wound up with an extra percent of vote share as a result of their efforts.

8. The Voto Duro. Historically, the PRI – the “party of the state”, the only one many older voters really knew for most of their lives – could count on a built-in block of unconditional voters. In the post-revolutionary era, this “hard vote” was organized in a series of corporatist structures, organizing workers, farmers and other non-salaried workers, such as taxi drivers, whose benefits were conditioned on their casting their votes, as a block, for the PRI. This structure is not what it once was, although it is still estimated that the PRI can count on a 10 million-vote bank. And it is a truism to say that, especially in low-turnout elections, getting out the core vote is key. Add to this the voto verde, or rural vote, still predominantly loyal to the ruling party in many parts of the countryside where the PRI is the only party with a genuine presence and where critical media does not reach. But what does reach is …

9. Televisa and Media Control. Televisa, the monster of Mexican television broadcasting controls some 68% of the Mexican television market and receives 70% of its advertising, mostly from federal and state governments. It uses this revenue to feed its massive audience a steady stream of denigrating game and reality shows; sensationalistic, misleading news programs; and, its crown jewel, a steady stream of maudlin soap operas that openly reinforce sexist, classist and racist stereotypes. In a country where an overwhelming majority receive what news they get from television, the control Televisa (and TV Azteca, the other member of the television duopoly) has over the flow of information is truly sinister. One only need recall the famous quote of Emilio Azcárraga Milmo, father of the current president of Televisa: “Mexico is a country with a modest class of very screwed people, who will always be screwed. The obligation of television is to provide these people with entertainment that takes them out of their sad realities and difficult futures.” And Televisa, of course, is not only strongly allied with President Enrique Peña Nieto, he is practically a creation of theirs. During the 2012 campaign, The Guardian newspaper revealed a secret pact between the television station and Peña Nieto dating back to 2005, when he was governor of the State of Mexico, to provide him with favorable coverage on its news and entertainment programs. In March of this year, popular independent journalist Carmen Aristegui was fired from her national radio program by her employer, MVS. The firing took place just in time to ensure that her program would not be on the air during campaign season.

10. The PRI Mindset. Former president Carlos Salinas de Gortari once (in)famously said, “The PRI is the way it is because that’s the way Mexicans are.” One doesn’t have to agree with him to recognize that the kind of actions we associate with the PRI – corporatist voting, vote buying and coercion, the use of public funds and programs to finance campaigns and condition votes, mafia-style intimidation tactics and even killings – occur in other parties as well, indeed, with some of the same people who jump from party to party as convenience dictates. What is clear is that the supposed “transition” to democracy that supposedly occurred in 2000 (between one right-wing party and another, hardly a transition in the sense of an alternation of right and left) has not occurred at the level of how party politics is practiced. And this is precisely why so many people, from the Zapatistas in Chiapas to the Oaxacan communities that practice town-meeting democracy, have turned their backs on a party structure which they perceive, reasonably, to be hopeless.

Ominously, there are signs that Peña Nieto is not only treating Sunday’s elections as a “victory,” but that he will use them as a pretext to crack down on those he didn’t manage to get into line in the first half of his presidency. Just yesterday, the government announced it will break off dialogue with the striking teacher’s union (CNTE). It is also to be supposed that the train of privatizations – with water the next item on the table – will move ahead with that much greater steam. Beware the electoral mirage: it produces consequences that turn out, in fact, to be very real.