En su número de septiembre, la revista Tierra Adentro publicó mi traducción de extractos del libro Personaggi precari (Personajes precarios) del escritor italiano Vanni Santoni, publicado por Voland Edizioni en 2013. Por razones de espacio, la revista no pudo incluir todos los personajes que traduje, entonces me complace reproducirlos a continuación.

(La traducción en Tierra Adentro puede verse en línea aquí.)

BARROZZO

El barón Barozzo da Montamaro hizo venir a trescientos mercenarios de Suiza para defender el feudo de vecinos que se habían vuelto hostiles. Cuando llegaron los suizos, encontrando el feudo tan indefenso y a la vez tan próspero, lo saquearon de inmediato, violando lo violable y poniendo al castillo bajo asedio.

Las débiles defensas fueron destrozadas en una hora y media y el asedio concluyó bebiendo el vino de los barriles rotos y sodomizando al barón Barozzo entre grandes risas.

BOB

Una vez Bob (y Sarah) llamaron a uno de esos payasos a domicilio. Cuando el tipo llegó a su patio, lo provocaron de manera vulgar; en cuanto hizo señas de irse, le bloquearon el paso y lo colmaron de palazos hasta hacerlo desmayar.

PENELOPE

Cuando era niña, dormía nueve o diez horas por noche. Durante la adolescencia llegó hasta trece, luego, hacia los veinte años, parecía haberse equilibrado. En cambio, ahora que tiene 29 años y vive sola, manteniéndose con réditos financieros, en el transcurso de pocos meses llegó a dormir dieciocho, diecinueve e incluso veinte horas al día. Cuando se despierta, Penelope está siempre de óptimo humor.

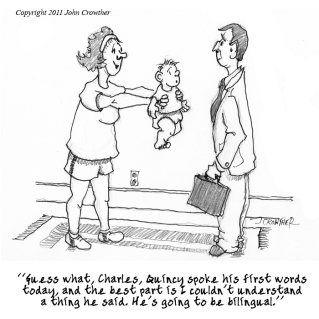

“An Homage to Precariousness” Photo: John Medina

UGOLINO

Hoy, no se sabe cómo, los sirvientes le compraron a Ugolino unos chocolates de leche de los que tienen relleno. Permanecerá de pésimo humor por días. En este momento, Ugolino está sacando el nougat del interior del chocolate con la manga de una cuchara de plata, gritando inmencionables insultos contra Suiza.

MAURIZIO

No contento con haber creado su propia página en Wikipedia, crea también una en Wikiquote, donde se reportan algunas de sus significativas afirmaciones, pronunciadas la noche del 31 de octubre de 2009 en el Bar Lerici (de Picchianti Adamo).

ANNA

Tengo que limpiar las ventanas, piensa Anna. Inmóvil como cera, desde la cama mira el vidrio. La oscuridad es una miríada de sombras, sedimentos de gotitas: cada una ha vivido medio centímetro, luego dejó atrás una idea de gris, más marcada hacia abajo. Se arrastra fuera de la cama, agarra una manzana. La sensación es mullida, desagradable. Piensa que en casa no hay provisiones, sólo manzanas marchitas y especias, cubitos de caldo, té y pasta de anchoa. Y pollo, hecho una carroña gris por estar en la congeladora sin bolsa. Se sienta a la mesa; cuando tiene que recibir a un hombre, saca los libros que considera le puedan hacer parecer más interesante, luego durante días no los vuelve a poner en su lugar. Hojea la poesía de Verlaine, ediciones Newton Compton tres mil nueve cientos liras, jamás leída, luego excava un sendero hacia el baño, mea, se levanta, se ve en el espejo con los ojos muy abiertos, exprime un poro ocluido en la nariz. En el vaso de los cepillos de dientes se está volviendo a formar el limo, piensa. Una vez encontró un pequeño gusano en el lavabo y tardó días en entender que venía del limo del vaso, un caldo primordial de minúsculos chorritos orgánicos y pasta dental y yeso caído que tiñe el pantano de gris.