A couple of nights ago, I saw the movie Rashomon, by Akira Kurosawa, for the first time. The central event of the film is the death of a samurai in the woods. But what made the film so epoch-making when it came out in 1950 was not the event in itself, precisely because there is no “in itself”: the film presents four plausible versions of what happened, told by two participants (a bandit and the samurai’s wife), an outside eyewitness (a passing woodcutter), and even the dead man himself told through a medium. And Kurosawa, thankfully, does not engage in the director’s prerogative of collapsing the quantum field of multiple possibilities into one authorized reality, but rather lets us roam freely through the uncertainty. Although he does provide us with a “resolution” of sorts – at the film’s conclusion, the woodcutter decides to adopt an abandoned baby even though he already has six children at home, providing some proof of humanity’s potential for goodness despite the atrocity in the woods drummed into us by four different tellings – the resolution is a false one, a palliative, and, existing as it does only in the frame story, is practically extra-diagetic. The woodcutter, his companion the priest and we the viewers may be mollified by the scene with the baby, but the death of the samurai is no nearer to the solution that it will never have.

The ability of narrative art to provide aesthetic satisfaction while daring to remain in the uncertainty zone is an important element in contemporary fiction. This authorial refusal to “tie things up” is one of the hardest things for average readers to accept, and, in the more artless cases, smacks to them of laziness. And rightly so. We may have left the era of the well-made play long behind, but if the author wants to ask us to assume the psychological cost of remaining in a state of ambiguity with respect to the narrative playing out in front of us on the stage, screen, or page, they’d better damn well make it worth our while. In Rashomon, the uncertainty ties us in compassion to the woodcutter, who, right from the beginning, while staring out at the rain, a party to the multiple versions of the killing, states over and over that he “just doesn’t understand”. That he is later the one who adopts the baby makes the conclusion, well, all the more satisfying of a palliative.

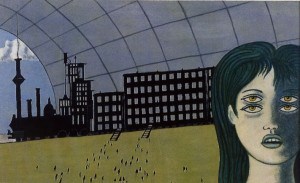

Sometimes, however, we are not even administered a palliative. In the Italian literature course I’m currently teaching, we recently read the story Qualcosa era successo (“Something Had Happened”) by Dino Buzzati. The terse title is remarkably descriptive: not only had “something” happened, but, whatever it was, it had already happened before the events taking place in the story, a nightmarish train trip up the entire Italian peninsula while hordes of people outside the windows flee in the opposite direction from some unnamed apocalypse the train’s passengers are heading helplessly into. When the train arrives at the deserted train station at the end of the line (I immediately thought of Milan’s Stazione Centrale, but even that is left undetermined), all the terrified passengers discover is the shadow of a train worker slipping out of view and, then, the voice of a single woman screaming for help. Her shouts bounce off the glass ceiling of the station with the “empty sonority of those places abandoned forever.”

I would argue that the fact that neither we nor the train’s passengers know what they’re heading towards heightens the dual effect of anguish and excitement. Buzzati is masterful at ratcheting up the tension as the train hurtles north: first, a single girl receiving news from someone running towards her, then several people running through a field, then people in building windows hurriedly packing their bags, then a boy shaking a newspaper at the train that a passenger only manages to grab a tiny fragment of, and so on until they arrive at the deserted station. If we knew what the actual cataclysm in question were, the story would be more like Bradbury’s “The Highway“, where the road fills with cars heading north from Mexico to the United States at the outset of an atomic war. Bradbury’s story is fine in its own right, and has stayed with me all these years since I read it in eighth grade, but I believe Buzzati’s story, precisely because it forces us to participate in an uncertainty that is not based on the outcome of concrete, future events but, rather, is built into the very parameters of the world he has created, cuts deeper.

Uncertainty is the revelation of our times. Schrödinger’s cat is neither alive nor dead, the position and momentum of a particle can never be known at the same time, the very foundations of all that classical mechanics taught was real have dissolved into an amorphous mass of mere tendencies. We can either look to literature as an escape into a world of a truly fictional certainty where we can all just sit back and push the catharsis button on our consoles. Or we can see it as a guide into a new world where the ontological decision-making is more democratic, one which must be, at least partially, of our own fashioning. As an anonymous English author wrote in the 14th century, only by entering voluntarily into a cloud of unknowing may we approach the divine.